Art I Summary of Periodic Trends1 Define the Phrase ââåperiodic Trendã¢ââ in Your Own Words

The surprising history of the discussion 'dude'

Many mutual terms in English have unexpected roots. Kelly Grovier explores the origins of 7 words coined in art history, including the political meanings of 'silhouette' and 'picturesque', and how 'mobile' became 'mob'.

W

Which came get-go, the chicken or the Fabergé egg – the globe itself, or the artistic expressions we use to see and draw it? While it is always observed with surprise when reality appears to imitate fine art, in fact the world of painting, drawing, and sculpture is responsible for giving us a bang-up deal of the language with which nosotros understand and clear our experience of beingness in the universe.

More like this:

- What will fine art look like in 20 years?

- How black women were whitewashed by art

- Da Vinci's lost masterpieces

Before anyone ever walked through a 'mural', an artist painted one. The word itself was devised in the early 17th Century not to draw an actual out-of-doors expanse of inland terrain or a gardener'southward manicuring of a natural scene. Rather, 'landscape' was created to denote a painterly illusion of such rural reality: the rendering in pigment on canvas of a 2D replica of hills and fields, rivers and trees – not the thing itself.

A quick glance dorsum at the words nosotros use every day to hash out our experience of the globe reveals a hidden reliance on linguistic communication hatched by art and artists. To dig deeper into the biographies of such ordinary words as 'silhouette', 'panorama' and 'dude' is to uncover surprising histories that change the way we empathize and appreciate their resonance and always-evolving meaning. What follows is a cursory exploration of some of the more fascinating coinages of words that have long since eased their way from their artistic origins into casual conversation.

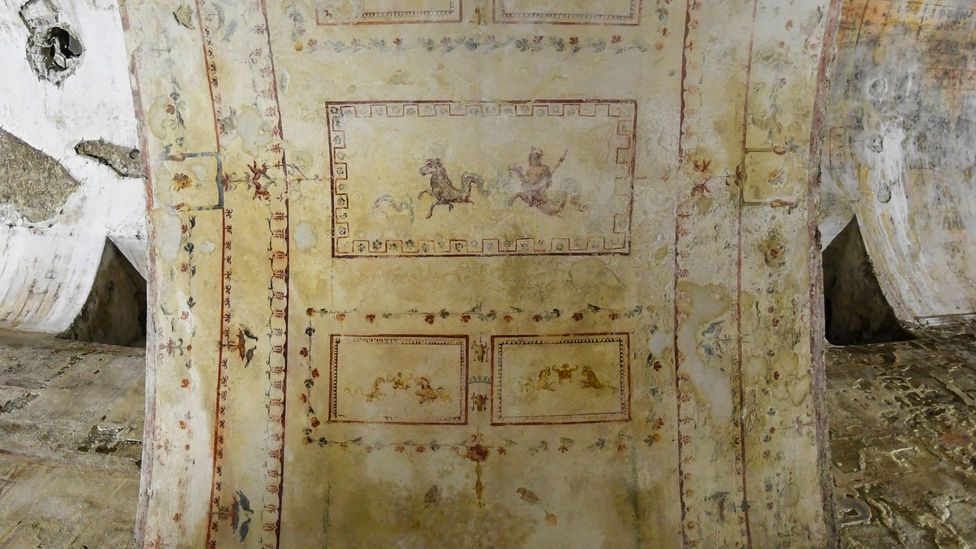

The word 'grotesque' refers to a infinite filled with wall paintings, in the Domus Aurea palace, discovered when a Roman youth fell through a crevice (Credit: Getty Images)

Grotesque

To the modern ear, calling something 'grotesque' is just a swankier way of maxim it'south grim and nasty. But this detail kind of ghastly nastiness has an intriguing cultural backstory – 1 that plunges the states deep below ground and into the time-buried rooms of a long-lost palace. It's thought that the word 'grotesque' likely owes its origin to weird wall designs that were rediscovered in Rome in the early on 15th Century when a immature boy brutal through a crevice in the city's Esquiline Hill.

The dark chamber into which the boy complanate was a basement of the fabled first-Century Domus Aurea – an elaborate compound built past Emperor Nero after the great fire of 64 Advertizement. Imagine the kid's shock when he plant himself surrounded past an elaborate braid of arabesque patterns into which were woven a macabre menagerie of hybrid human-beasts. The infinite itself was labelled a 'grotto' (pregnant 'cave') for the manner in which it was accessed by the many visitors it shortly attracted (including Michelangelo and Raphael), who were variously lowered downwards past ropes or left to crawl within. 'Grotto' in plough gave birth to 'grottesco' (or 'resembling a grotto'). By stripping away its sense of shadowy mystery and retaining only its hint of hideousness, our mod usage of 'grotesque' has muted the word's edgy magic.

'Silhouette' was coined in response to the austerity measures of a French treasury minister in the 18th Century (Credit: Getty Images)

Silhouette

'Silhouette' isn't then much a word one says equally whispers. Like a compressed one-word poem, silhouette's syllables respire with an easy elegance that seems utterly in harmony with the exquisite simplicity of the miracle for which information technology stands: the fleeting shadow of someone cast confronting a white wall. That is what it means, right? In fact, the word's origin is rather less liltingly lyrical than you might guess. It was coined in the 18th Century equally a kind of sarcastic dig against the economic policies of Louis Xv'due south Treasury Primary, Étienne de Silhouette.

In an effort to bring France's swelling debts under control, Silhouette proposed taxing those who displayed signs of conspicuous wealth, such equally the ownership of expensive works of art. Before long, anything that smacked of extreme frugality was said to be washed 'à la Silhouette', including the product of inexpensive likenesses of sitters cut out from black paper instead of more elaborately painted portraits. It wasn't long earlier the nickname 'silhouette' stuck, the music of the discussion long outliving the snippy circumstances of its coinage.

'Picturesque' – such equally Mountainous Mural with Ruin by William Gilpin – could have been an artistic movement to forestall revolution spreading from France (Credit: Getty Images)

Picturesque

'Picturesque' is the word we attain for to describe the allure of a charming vista or natural scene. Surely it is a discussion at furthest possible remove from the realm of propaganda? In fact, it has a rather sinister political past. Derived from the Italian word 'pittoresco', 'picturesque' was seized upon at the end of the 18th Century by upper-class British artists who had been inspired by the luminous Italian landscape paintings they'd encountered while visiting the groovy hubs of European civilization on what became known as The One thousand Tour.

But the 'picturesque' paintings that artists such every bit William Gilpin began to create differed strikingly from the wide-open and liberating vistas you find in paintings by such masters of 'pittoresco' style every bit Claude Lorrain or Salvator Rosa. The winding paths and meandering rivers that lead one'due south middle from the shadowy foreground in a Claude painting, to the soul-soaring horizons in his sun-soaked distance, are suddenly shut downwards – the liberating journey of the centre is blocked.

Some cultural critics have suggested that proponents of the British picturesque may have been motivated by fear of political revolution spreading from France to England, and then sabotaged its power in order to continue the aspirations of observers of their work in check. No wonder the US transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson, who believed in the ascent of spirit, once asserted: "pictures must not be too picturesque".

In 1789, the artist Robert Barker invented a cylindrical vista that surrounded the viewer: at offset, a panorama was something that enclosed rather than a space without limits

Panorama

Say the give-and-take 'panorama' and the whole world opens up. Its sprightly syllables launch the imagination outward as far as the soul can see into a whirling and unbroken orbit of near omniscience. A 'panorama' implies a vertiginous rising and visual spin that places each one of us at the very centre of all we survey. How foreign then, to observe that the discussion itself was in fact coined to describe an entirely indoor, cloistral and windowless experience.

The word was introduced effectually 1789, the year the Bastille prison fell, by the artist Robert Barker to describe a contraption for which he'd sought a patent two years before. The invention, modestly described in the application as 'Apparatus for Exhibiting Pictures', involved enveloping an observer in an enclosed, circular bedroom, or rotunda, whose cylindrical walls were covered with a seamless and extensive depiction of an encircling vista. A popular panorama that Barker installed in London's Leicester Square attracted visitors for 70 years, from 1793 to 1863. The offset panoramas weren't panoramic at all, only pretty prisons.

The playwright and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire coined the give-and-take 'surreal' when describing a new ballet by Erik Satie and Jean Cocteau (Credit: Getty Images)

Surreal

These days, annihilation that's out of the ordinary is called 'surreal'. A writer for the Washington Post this month described the trend of scriptwriters suing their own agents equally a "surreal turn". The adjacent day, a journalist for the Hollywood Reporter characterised the printing conference that the United states of america Attorney General held before releasing the long-awaited report on Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election as a "surreal Television receiver presser". It wasn't always so. The French intellectual who coined the give-and-take 'surreal' a century ago had rather higher hopes for his linguistic invention.

Writing in a letter dated March 1917, the playwright and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire attempted to capture the essence of a new ballet by Erik Satie and Jean Cocteau. "All things considered", Apollinaire said of the production of Parade, in which performers pranced around in bizarre, boxy costumes designed past the pioneering Cubist painter Pablo Picasso, "I think in fact it is better to adopt surrealism than supernaturalism, which I first used."

Apollinaire would promote his minting of the word 'surrealism' (by which he hoped to capture the ballet's 'visionary' quality) by enshrining it in the programme notes, which he was invited to write. Now floating in the air of avant-garde Paris, the term was eventually picked up by artists (such as Salvador Dalí and René Magritte) fascinated by the power of the unconscious mind to produce images, symbols, and statements that supervene upon the realities of ordinary reason and experience. Rather than a derogatory synonym for 'preposterous', 'surreal' was intended to signify our hole-and-corner access to universal truths.

French artist Marcel Duchamp applied the word 'mobile' to a kinetic piece of work past Alexander Calder in 1931 (Credit: BBC)

Mobile

Few words are as mobile in their meaning as 'mobile'. Handy shorthand today for 'mobile telephone', the word was also an abbreviation in the 17th Century for the insulting phrase 'mobile vulgus', used condescendingly to describe the hoi polloi. Eventually 'mobile', as a stand up-in for riffraff and rabble, was compressed further still to the slur nosotros notwithstanding use today: 'mob'.

In 1931, the Us sculptor Alexander Calder and the French advanced pioneer Marcel Duchamp added another twist to the word'southward meaning. Not knowing what to telephone call his new kinetic works, comprised of abstruse shapes bobbing with perfect balance from cord and wires, Calder asked Duchamp for his communication. Duchamp, who'd already shocked the world 14 years earlier past declaring a urinal a work of art, did what Duchamp did best, and re-appropriated a readymade construction past giving it a new spin. Voila: 'mobile'.

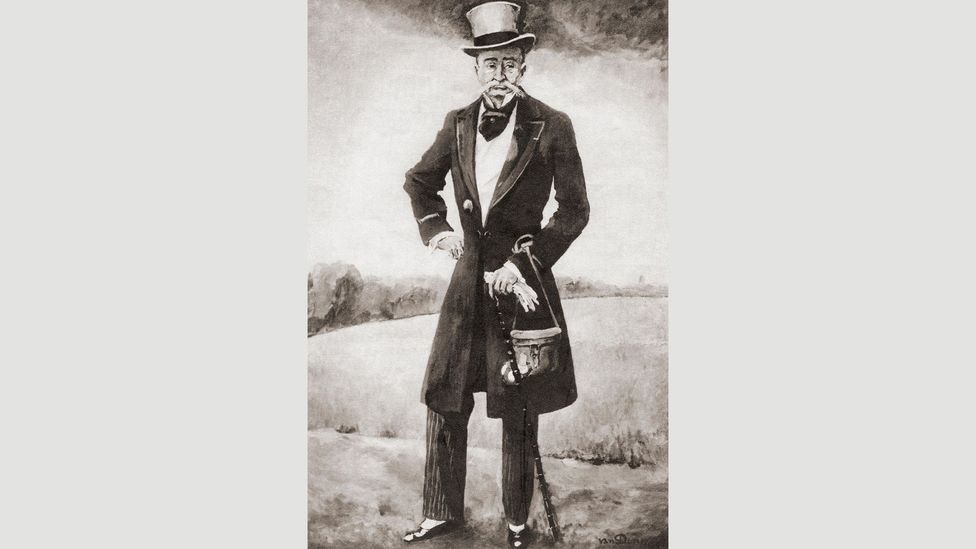

The word 'dude' originally applied to American dandies – such every bit Evander Drupe Wall, pictured – in the 19th Century (Credit: Alamy)

Dude

Before there was 'bro', there was 'dude': that informal address that slaps you lot on the dorsum with ane hand, gives you lot a White Russian with the other, and says, 'hey, I woke up at noon also, man'. For the past xx years, Jeff Bridge's portrayal of The Dude in the Coen Brothers' film The Big Lebowski (1998) has epitomised the seductive spirit of dudeness. Dishevelled, stoned and disorientated, The Dude's laid-back attitude is difficult to square with the artsy origin of the word itself, which seems to have entered popular discourse in the early 1880s as autograph for foppishly turned-out male followers of the Aesthetic Movement – a short-lived artistic vogue that championed superficial fashion and corrupt beauty ('art for art'south sake') and was associated with ostentatiously-attired artists such every bit James McNeill Whistler and Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Information technology's thought that 'dude' is an abbreviation of 'Putter' in 'Yankee Doodle', and probably refers to the new-fangled 'bully' that the song describes. Originally sung in the late 18th Century by British soldiers keen to lampoon the American colonists with whom they were at state of war, the ditty, by the end of the 19th Century, had been embraced in the US equally a patriotic anthem.

By then, an indigenous species of fastidiously over-styled popinjays had emerged in America to rival the British dandy, and information technology is to this new breed of primly dressed aesthetes that the term 'dude' was fastened. Over time, the silk cravats and tapered trousers, varnished shoes and stripy vests worn by such proponents of the trend every bit Evander Berry Wall (the New York City socialite who was dubbed 'King of the Dudes') would exist stripped away, leaving little more than a countercultural attitude to define what it means to exist a Dude (or an El Duderino, if yous're not into the whole brevity thing).

If you would like to annotate on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us onTwitter .

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , chosen "If You lot Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked choice of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Fri.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20190508-the-surprising-history-of-the-word-dude

0 Response to "Art I Summary of Periodic Trends1 Define the Phrase ââåperiodic Trendã¢ââ in Your Own Words"

แสดงความคิดเห็น